Two Buried Ships

When construction work happens in San Francisco, traces of the city’s history are often uncovered. During a project in Visitacion Valley to upgrade old sections of the Sunnydale neighborhood sewer lines, archaeologists found two ships—a scow schooner and a barge. The ships, more than 100 years old when found, were buried 15 feet below ground!

In early February 2011, archaeologists from Far Western Anthropological Research Group monitored the sewer project and watched for traces of San Francisco’s buried history. When a backhoe unearthed pieces of wood, work on the sewer line temporarily stopped. As the team’s historical archaeologists (R. Scott Baxter and Rebecca Allen from Environmental Science Associates [ESA]) carefully uncovered an arrangement of posts and planks, excitement grew. A support beam, large timbers, and more planks were revealed – what had they found?

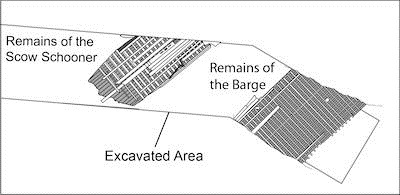

Staff from the National Maritime Museum arrived on the scene to view the find and confirmed what the archaeologists had suspected—they were excavating part of a scow schooner. The back end (stern) of the ship was in the sewer trench, but the front end (bow) was buried outside of the trenched area. The archaeologists soon uncovered a second ship nearby—a wooden barge. These two ships had been supplying San Francisco with important goods during the late-nineteenth and early-twentieth centuries. The scow schooner had probably carried such things as hay, lumber, and sacks of salt. The barge might have carried barley, wheat, or anything else the growing city needed.

"The discovery and excavation of a buried ship is an exciting and important once-in-a-lifetime experience for an archaeologist."

Dr. Brian Byrd

Archaeological Team Leader

Far Western Anthropological Research Group, Davis, California

"These were the flatbed trucks of San Francisco Bay from the late 19th and early 20th century. They're largely forgotten now, but these scow schooners moved the goods that built the city and the Bay Area economy."

Jim Delgado

Author, Gold Rush Port: The Maritime Archaeology of San Francisco’s Waterfront

Archaeologists from Far Western and ESA were able to uncover the middle and rear sections of the ships, but the timbers were waterlogged and in poor condition. The wood rapidly deteriorated when exposed to air, so instead of trying to remove parts of the ships, the archaeologists documented both finds in place. Since such ships are rarely found, the team focused on recording the construction details of the ships and gained important insights into building techniques. Watch the archaeologists in action!

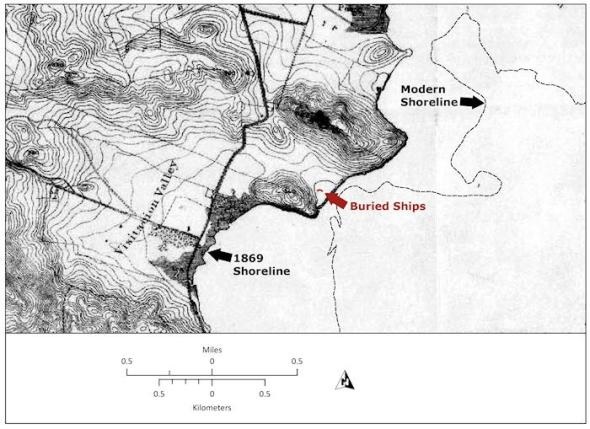

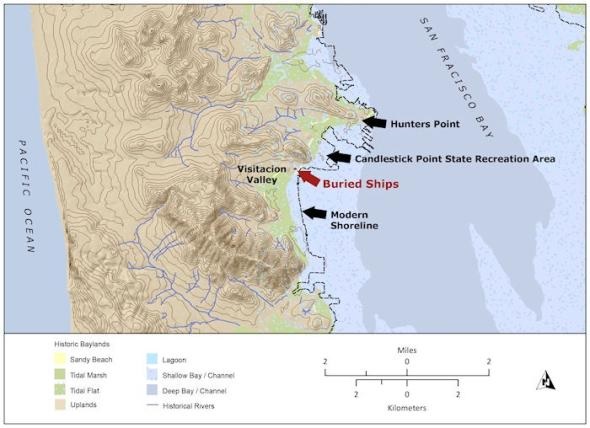

They also studied the land in order to understand how and why the ships were buried. For thousands of years, this area along the western edge of San Francisco Bay was underwater. It had been the floor of a small cove. Native Americans probably used the cove and nearby seabed for generations to gather oysters and other food.

During the Gold Rush, the land was still under water, but as San Francisco grew, so did its shoreline. The shoreline “grew” because fill and debris were being dumped into the bay. As railroads and automobiles replaced ships delivering cargo, the abandoned vessels began accumulating along the San Francisco shoreline.

A 1938 aerial photograph shows that the small cove south of Candlestick Point had been filled in. Many abandoned ships can be seen in the photograph, anchored to the east. Near the cove, several buildings and a ship are visible along the shore. This ship is approximately the same size as the scow schooner found in 2011— it may be the same one!

During the 1930s, Candlestick Cove was used as a ship breaking site. Ships were hauled onto shore and stripped of valuable wood, metal, and other materials. These useful parts were recycled for other uses. The wrecks were often burned and then abandoned to become part of the rubble used to create new land. Both of the ships found during repair of the sewer were what remained of broken and salvaged ships. They were “recycled” into a new use as fill.

Archaeological discovery of the two ships allowed us to learn more about shipbuilding and about San Francisco’s ship breaking and recycling during the early part of the twentieth century. The discovery also revealed a moment in time of San Francisco’s past—a period of transition as the city grew and new technologies overtook the past. Railroad cars, trucks, and automobiles had replaced scow schooners and barges for delivering goods throughout California.